Read The Infinite Highway, the outline of a book on Project Mercury by Robert B. Voas

NASA: Project Mercury

Read the NASA Oral History interview with Robert B. Voas

When the American space program started, its staff had extensive engineering expertise but little capacity in human factors and aviation medicine. The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) turned to the armed forces for this medical expertise. Because Captain Norman Lee Barr was the Navy’s leading expert in high-altitude medicine and Lieutenant Voas was his principal assistant, Voas was transferred to the space program. Voas joined NACA in September 1958, just prior to the establishment of NASA on October 1, 1958. Voas became the Head Astronaut Training Officer.

As part of the Space Task Group, Voas helped conceptualize the criteria for the selection of the original seven astronauts for Project Mercury. In January 1959, Voas—along with Stanley C. White and William S. Augerson—screened 508 service records and found 110 men who met the minimum standards to become an astronaut. The list of names included 5 Marines, 47 Navy aviators, and 58 Air Force pilots. The group of 110 was divided into three groups, but by the completion of round two, there were enough volunteers that group three was never called. Through testing, these 69 men were further pared down to 32 and then to 18. By the middle of April, America’s first 7 astronauts had been selected.

Voas became the Training Officer for Project Mercury and Assistant to the Director of the Manned Spacecraft Center. He supervised the training of the seven astronauts. The astronauts were exposed to every imaginable experience they might encounter during space flight: the parabolic flights in the bay of a cargo plane simulated weightlessness; centrifuge tests exposed the pilots to the high acceleration (g forces) of the launch phase of a space flight; and altitude-control simulations honed their ability to keep the spacecraft from tumbling across the three dimensions of pitch, yaw, and roll. The training was designed to demonstrate that the project was safe and that NASA was ready to fly. It also had to satisfy President Eisenhower, who did not want manned space flights to go forward until it was proven safe.

Voas wrote the Project Mercury Astronaut Training Program, the first of its kind, which was presented at the Symposium on Psychological Aspects of Space Flight held in San Antonia, Texas, May 26-27, 1960. (See also https://history.nasa.gov/SP-45/ch10.htm)

On May 5, 1961, Alan Shepard was launched into space aboard Mercury-Redstone 3. Although this 15-minute sub-orbital flight, less than a month after the Soviet Union put Yuri Gagarin in orbit, seemed unimpressive, it showed that Americans were still in the space race. In July 1961, astronaut Gus Grissom repeated Shepard’s brief hop into space. After several delays, John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth in February 1962. Between 1961 and 1963, six manned spacecraft flew as part of Project Mercury. Many years later, Voas received the W. Randolph Lovelace Award for Significant Contribution to Aerospace Medicine.

Voas later proposed the selection process for the Gemini astronauts.

Voas (center) with Mercury astronauts for weightlessness training

Voas (right) with Mercury astronauts and flight surgeon Dr. William Douglas at Langley Research Center, 1960

Voas (left) at the debrief of Alan Shepard on Grand Turk Island (near the Bahamas), May 6, 1961

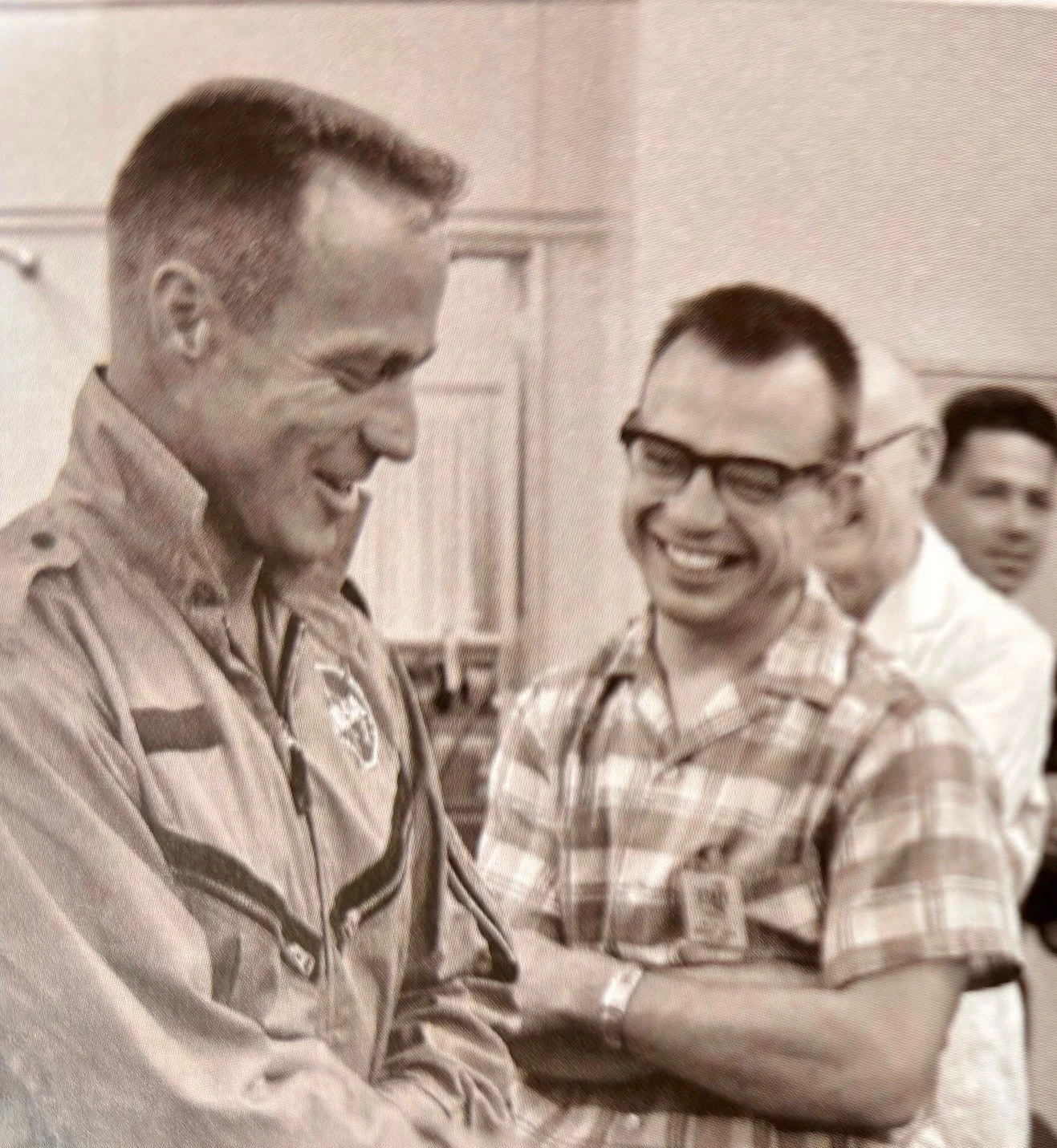

Voas with Scott Carpenter, 1962

Voas with Kris Carpenter Stoever (Scott Carpenter's daughter), 2024